I often observe that H.P. Lovecraft is the single largest influence on my writing, but I don’t talk or write as much about Charles Baudelaire, specifically how his collection of prose poems, Le Spleen de Paris, completely changed the way I thought about story telling.

I often observe that H.P. Lovecraft is the single largest influence on my writing, but I don’t talk or write as much about Charles Baudelaire, specifically how his collection of prose poems, Le Spleen de Paris, completely changed the way I thought about story telling.

Although famous for the lovely and wicked Les Fleurs du mal, Baudelaire’s unusual experiment into the world of short prose remains, for my money, one of the most bizarre and beautiful collections of short fiction.

I know: technically, the 50 prose poems — or petits poemes — in Le Spleen de Paris are not short stories. They are often only two or three hundred words in length, with notable longer exceptions. They do not follow the rules of a short story in that they are unconcerned with an arc, or with the beginning/middle/end model hammered into us from a very early age. The characters are often strange, sometimes ephemeral simulacra of a mood or tone rather than people with whom we should identify. Often, the requisite conflict is poetic rather than narrative; meaning it is symbolic and almost never mundane.

These qualities of Baudelaire’s prose poems endeared him, well after his death, to H.P. Lovecraft and Andre Breton, two men with the intellectual vigor to recognize the beauty in the terror of dreams. In 1927’s Supernatural Horror in Literature, Lovecraft wrote:

Of the former class of “artists in sin” the illustrious poet Baudelaire, influenced vastly by Poe, is the supreme type; whilst the psychological novelist Joris-Karl Huysmans, a true child of the eighteen-nineties, is at once the summation and finale.

Baudelaire, smitten by Poe’s power as a writer of short fiction, contributed to Poe’s popularity in France by translating everything he wrote. It was the golden age of the French novel, and Baudelaire wanted to master it. But, as Rosemary Lloyd points out in her introduction to the 1991 Oxford University Press edition of The Prose Poems and La Fanfarlo:

His critical writing reveals a determination both to understand the mechanisms used by novelists and short-story writers, and, typically, to make better use of those same mechanisms. But while his ambitions were boundless, the pragmatic difficulties of completing a full-scale novel seem to have been beyond him, partly for practical reasons associated with the chaotic and often sordid life-style his financial position forced him to adopt, and partly, there can be no doubt, because of his own temperament.

When I wrote before that in Le Spleen de Paris characters are often strange, sometimes ephemeral simulacra of a mood or tone rather than people with whom we should identify, I was thinking of Huysmans, mentioned also by Lovecraft in his passage. Huysmans’ À rebours is a challenging journey through the mind of Jean Des Esseintes, a decadent to rule all decadents. In the novel, Huysmans uses his astonishing vocabulary and command of French to paint grim and pessimistic events in a way that are, in themselves, a decadent joy to read. On a much smaller and more accessible scale, across the length of 50 short prose poems, Baudelaire achieves much the same thing. The DNA strand is there: Poe influences Baudelaire, who influences Huysmans, all of whom influence Lovecraft.

Which brings us to me. You knew it would.

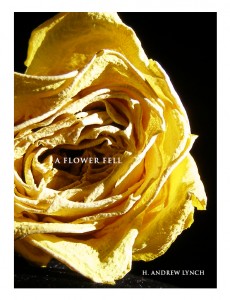

I can’t tell you exactly the first time I read Le Spleen de Paris, but it was in Chicago in the very early ’90s. Shortly after reading it, when I was still in the magnificent throes every young writer goes through — nothing is impossible, I am a sponge, what came before me is food for the muse — I began writing my response to Le Spleen de Paris. The first prose poem I wrote was called “A Flower Fell” and was a direct reference to Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du mal. The title was meant to be a short sentence, and it was some time before I realized I had actually evoked in my title a tone that would largely embody everything I wanted to do with this response. A man down, a woman aggrieved, a country divided, a flower fell.

It was incredibly important that I show my own voice despite the stylistic fealty I at the time felt to Lovecraft, Poe, and Baudelaire. From “A Flower Fell”:

A form, lost now to memory but which was once vivid when my mind was bright and alive to the things children see, blossomed from the fading orange ash and offered its gullet to the stars.

Eventually, I decided that my collection would be called A Flower Fell. I wrote about fifteen of these poems, many of them pastiches or outright experiments in the use of language to create an effect (rather than to tell a straightforward story). Baudelaire’s “A Hemisphere In Your Hair” inspired my “There’s a Sidewalk in your Face.” His “The Generous Gambler” was a tonal foundation for my “Dumb Doors and Windowpanes.” But after time, I felt I had exhausted the experiment, so I lost interest in it.

Fifteen years later, reacquainting myself with Le Spleen de Paris, I found a new well of stories to be told. So, I wrote another dozen or so prose poems. The differences between those poems I’d written as a young writer and those I wrote after acquiring wisdom and cynicism are, while not stark, tonally distinct. The latter works are, perhaps, less whimsical, although they are better written. Several of the former works read like startling amuse-gueule, while the latter ones favor the gluttonous palate.

Looking back on these prose poems from the ancient present, I can’t help but think of Virgilio Piñera, the Cuban writer who died in obscurity after being censured by Castro’s government. It is unlikely that you will find many readers familiar with Le Spleen de Paris, and even less likely that you will find fans of Piñera, author of the unforgettable short-story collection, Cold Tales.